Beneath the Duomo, Florence

Stunning arches and mosaics © A. Harrison

I stood in a crypt which held remains of houses from the old Roman town Florentia, plus those from a fourth century Christian church and a medieval cathedral. The space around me place felt enormous, yet it was dwarfed by Florence’s Duomo who, with feet buried in these foundations, rose to the sky above me.

Despite the crowds milling outside and the long wait to enter, I’ve always adored Florence’s Santa Marie del Fiore. Whenever I walk through her doors I’m filled me with peace and serenity, from her patterned marble floors to her vaulting ceilings. Standing under Vasari’s dome never ceases to till me with wonder.

Yet hidden to one side just near the entrance are stairs leading from the Duomo down to a long hidden crypt. Roman mosaics line part of the floor, and a section of the work tower built by Brunelleschi remains.

In a city as old as Florence, the Duomo is not the first building on this site. The Roman town Florentia, established in 59 BCE by Julius Caesar rapidly became a major trade centre after he granted land here to his veteran soldiers. Extensive remains of the old town, including sections of old houses, remain below the Duomo.

Sometime in the 4th and 5th centuries ACE the Church of Santa Reparata was constructed on the site, possibly over an older church. Although there are competing theories, it is believed Santa Reparata was built to celebrate the Christian victory over Radagaisus, King of the Goths, sometime around 405 AD. Early Christian mosaics predate the building, and there are the remains of an old altar.

Remains of old walls © A. Harrison

The Basilica of Santa Reparata was central to the life of early Florence. Prior to the construction of the Palazzo Vecchio, the church was used by the Florentine Parliament as a meeting hall. Extensively rebuilt and enlarged over the centuries, diagrams in the crypt show the sheer size of the Duomo in comparison; the Basilica of Santa Reparata was approximately only one sixth the size of the later cathedral.

A path winds through the display, past Roman and Medieval artefacts such as carvings, tombs, effigies, glassware - even the remains of a Roman road. The mosaic floor is in a polychrome geometric pattern of hexagons, diamonds and Solomon's knots (according to the brochure I collected on entering. I don't claim to be an authority on Solomon's knots.) On the floor of the central nave of the old church is a stunning mosaic of a peacock, near names of fourteen donors who contributed to the construction of the basilica. They are listed according to the number of Roman feet they financed. Intriguingly, the work is attributed to African craftsmen; at that time, Fiorentina had close trading and cultural ties to Northern Africa

A large number of tombs have survived the centuries, many with carved headstones. One belongs to Giovanni Di Alamanno de’Medici, who did in 1532; it is believed a pope has been buried here. Filippo Brunelleschi was held in such reverence by the Florentines he was buried near the entrance. The carving on his tomb reads: ‘corpus magni ingenii viri Philippi Brunelleschi fiorentini ‘ (here lies the body of the great talent Filippo Brunelleschi of Florence). Although Giotto’s body has never been found, a plaque matching the description given by Vasari in his Lives of the Artists of Giotto’s burial place has been uncovered.

In 1379, the decision was made to completely demolish the Basilica of Santa Reparata to make way for the new Duomo, which remains the largest medieval cathedral in Europe. Dante used to sit in the square and watch as she was being built; artists such as Donatello had their studios on the Piazza Duomo. The Duomo remains a symbol of Florence; for me it is a place of serenity, a sight which brings me joy and memories from wherever I see her. Now I also remember what lies beneath, and from what history she arose to challenge the heavens.

Enjoy my writing? Please subscribe here to follow my blog. Or perhaps you’d like to buy me a coffee? (Or a pony?)

If you like my photos please click either here or on the link in my header to buy (or simply browse) my photos. Or else, please click here to buy either my poetry or novel ebooks. I even have a YouTube channel. Thank you!

Plus, this post contains affiliate links, from which I (potentially) earn a small commission.

The Literary Traveller

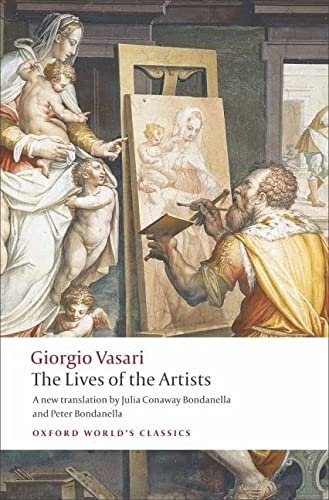

Vasari’s The Lives of the Artists is credited as the first work of art history. A contemporary of Michelangelo (whose talents, according to Vasari, including making the world's best snowmen), Vasari was himself a famed artist and architect.

Although biased towards the Florentine painters (in the first printing Titan did not rate a mention), Vasari’s work remains an amazing window into the Renaissance world. Indeed, Vasari was the first to use the word Renaissance in print.

Vasari also peppers his works with delightful bits of gossips and observations of the artistic life:

(these)rough sketches, which are born in an instant in the heat of inspiration, express the idea of their author in a few strokes, while on the other hand too much effort and diligence sometimes sap the vitality and powers of those who never know when to leave off.

The book is perfect for reading after a day of exploring the unending museum and art gallery which is Italy.